What is good management and how do we get it?

Understanding the worst-defined domain in business.

“Management” is perhaps the most poorly understood concept in business. It’s uneven in quality, hard to train, and harder to measure. People say all kinds of insane things about it, like “a manager’s job is to run meetings” or “management’s job is capital allocation”. Mismanagement, when it happens, is pervasive and tends to endure until there’s a pattern interrupt (CEO fired, some other crisis or catastrophe). Yet we all agree good management is key to successful businesses, and we know what it looks like when we see it.

Over the past 6 months I’ve met more than 40 managers, ranging from first timers to experienced professionals, to learn about their people management practices. All had a different view on it, typically informed by their local environment. Unsurprisingly, management quality was hugely variable and uneven both across and within organisations.

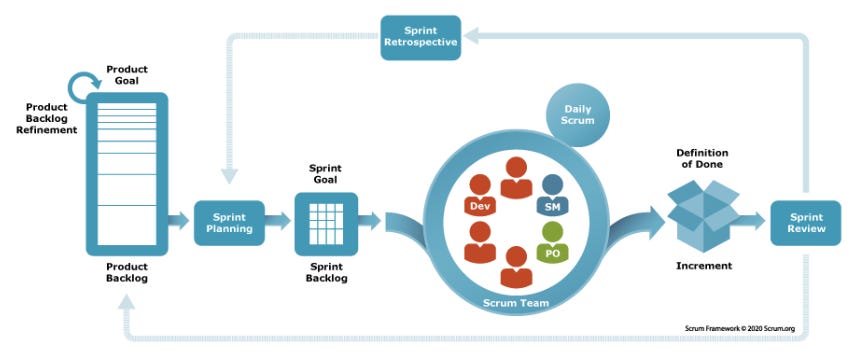

Unlike most other fields that have moved beyond a craftwork approach with modern frameworks, what I found is that people management is still basically artisanal, sometimes without even the apprenticeship. Pretty much 100% of the managers I have spoken with learned through a homebrew combination of books, observation, and learning by doing. For those with a clear approach, it came initially from a framework like Scrum which provides an objective “right way” but does nothing to alleviate the ambiguities of leading people well.

In this article I want to define what management is, how to manage, and where good management comes from.

Management is a force multiplier

The first thing to understand about Management is that it is a force multiplier. “Good management” creates no value in and of itself - what use are management skills without an organisation?

Management multiplies or divides an organisation’s commercial efforts, resulting in more or less value being created.

Management compounds

The second thing we need to understand is that management compounds. A well-managed organisation will become steadily, almost-imperceptibly more impactful until it dominates its niche. A poorly managed organisation will gradually become slower and slower until one day it simply stops; consumed by its own internal mechanisms.

As a result, it’s often hard to see the positive impact of improving management in the day to day, and over a given timeframe, management quality usually “doesn’t matter”.

Improving your management quality by “10%” will not increase profits by 10%. It will make your organisation more focused and easier to run, though, and make it much more plausible that you will grow profit.

Realistically the goal is to build a business so strong that “any idiot can run it, because sooner or later, one will”. Between now and then, it is enough to understand that management compounds and is a multiplier on your efforts.

What is Management?

So. What is this management thing and why do people struggle with it? Here is an example from Patty McCord’s “Powerful” of a small company trying to train its managers.

“We need better managers.” Cool what are you going to teach them? “Management.” Yeah, but what specifically? “…Managing.” OK but which aspect of management are they worst at? “Well there will be a full training program, of course.”

I’ll link another example here from the early days of Paypal, which was famous for having “no management”. Of course if you read the example, what you will see is actually a crystal clear and rigorously enforced approach to managing. (What Paypal was really trying to avoid is Bureaucracy, which is a technology for enforcing consistency, but that is a story for another time).

Why do companies suck at this? Often, they arrive at their definition of management by starting with the unit of work (e.g. running meetings, managing a budget) and then using that to define the job - which is completely backwards. Meetings are a tool that a manager can use to manage, they are not the output of a successful manager.

Defining Management:

Since 2019, I have reviewed a broad cross-section of the literature (well over 100 sources), and propose a new definition:

“Management is the craft of solving problems by applying and adding leverage to an organisation’s efforts.”

There are three components to this:

Applying Effort: We (the imperial We, the organisation) employ all these people, they must do useful things that add value instead of spinning their wheels doing easy things, things that don’t matter, pulling in opposing directions, etc etc. The easiest way to define “value” is “increase revenue/reduce costs” which I use in this article as shorthand, but obviously there are layers to this (e.g. “reduce the chance of being nuked by lawsuits”, “optimise working capital to free up cash for investment” and so on).

Adding Leverage: Managers typically produce less primary output and command a salary higher than an individual contributor (“IC”). Adding a manager to a team increases costs but value created does not necessarily increase (multiplier). Output goes down as the friction of operating an organisation at scale increases. Simplistically if you are a manager and you manage five people, they must be at least “20%” more effective (higher revenue/lower costs) simply to justify your salary before you start adding value.

In practice this usually means you must alleviate 20% of organisational decay (coordination & communication burden), but the idea is the same.

Solving Problems: The work done by the team must actually solve valuable problems (build the widget, sell the thing, reduce the risk, win the war, etc). The “what” of your role - the problem you solve - must be defined for your function. E.g. I am a sales manager; the problem I solve is making sure we are selling a lot of stuff at good margins. I am an operations manager, the problem I solve is making sure we process things quickly and with high accuracy. (Some people take issue with the word “problem” and prefer to phrase this as “pursuing opportunities”, and it could be framed this way if that works for you.)

The essence of management is: Applying Effort, Adding Leverage, Solving Problems.

How do we manage?

Now that we have defined What management is, How do we do it? At the end of the day, there are really only two ways to manage. Managers manage by:

A) Creating and maintaining positive feedback loops, and

B) Short-circuiting negative feedback loops.

Breaking that down further:

A) Creating and reinforcing positive feedback loops. To give one example, performance management is a feedback loop process. We source and hire someone good who can add value, train them to get up to speed so that they can contribute more value faster, set a bar for performance and measure it, they do good work, value is created (higher revenue / lower costs), they are rewarded for performance, we move the performance bar higher, if we do this for everyone the organisation gets easier to run & more effective, we can become more ambitious and aim higher, etc → ∞ ad infinitum. The more the loop spins, the better the company gets.

B) Short-circuiting negative feedback loops. In the inverse example, imagine we have someone who feels disrespected in their role. They become prickly and defensive, are difficult to deal with, people interact with them less, they are left out of discussions and receive information more slowly, their job gets harder, the quality of work that depends on their input reduces, outcomes deteriorate, they feel more disrespected, become pricklier, this ripples across the org and makes everyone else’s job harder → ∞ ad infinitum. The more the loop spins, the worse the company gets.

All of the things that people think managers do - making decisions, communicating, setting goals, managing performance, maintaining system/cultural integrity, budgets, hiring, quality control etc, are tools that fit into the above buckets. It is a bit like gardening; the tree must grow healthy and strong, but whether you should water it or spray for insects is a different question.

Having defined management, we can take it down a level into specific techniques people use to actually manage. Some examples:

Meetings: A crisp meeting gets everyone on the same page, and makes sure we are all rowing in the same direction and not pulling against each other, i.e. we are Applying efforts to problems.

Communicating: Regular updates share useful information, such as goals, changes to policy or circumstances. This allows us to focus our efforts and minimise the amount of rejection & rework, i.e. we are adding Leverage and Applying effort.

Goals / Targets: These make it clear to everybody what good performance looks like. They help us Apply effort, stretch, and add Leverage.

Budgets / Resource allocation: Understand how much money we have available, how much we are spending, and on what (i.e. a tool for Applying Efforts).

Capital Allocation: Literally where do we Apply our efforts, what kind of return (Leverage) do we get on these, and can we increase this? Management is not capital allocation. Capital allocation is a tool a manager can use to manage.

Viewed like this it becomes clear that all the “things” you do as a manager are tools that either Apply Effort or Add Leverage, and either maintain/reinforce positive loops or short-circuit negative ones.

Yeah, but how do I actually manage?

I am going to give you another non-answer here. If you really want to know the mechanics of how to run a team on a day-to-day basis with an objectively right answer, then just go do a Scrum course or similar.

The true answer, in my view, is that a manager’s belief system determines how they manage. This is one of the least explicit parts of management that in my view causes the most conflict.

Here’s a simple example:

leaders eat first; bosses are special, can work less hard and get special perks tied to their position (e.g. dedicated car space).

leaders eat last; bosses are not special, should work as hard as their team, and not receive special perks tied to their position (use the carpark with everyone else).

Very few organisations will ever tell you “we bosses are way more important than you worker drones” but many organisations believe this, and this obviously influences the way that companies manage and their results - especially when they message the opposite.

Let’s look at another example:

People are replaceable; people are cogs in a machine, we do not need to treat them with any special care, and if they leave, we can simply find another one to work for us.

People are not replaceable; people are not cogs in a machine, they are unique and an untapped well of potential and we must do our part to help grow that potential for both our benefits.

What’s interesting with this example is that both are obviously true - people are replaceable cogs in a machine, AND people are a unique well of potential. However, most managers lean one way or the other in their beliefs, and this flows through and informs how they act as managers, how their team performs, and the types of people issues they have.

Managerial belief systems

Phrased differently, the way a manager manages - how and when they apply their tools, the types of problems they run into - is mostly determined by their belief system.

If you believe that people cannot think for themselves and must be told what to do, largely you will be proven correct! Consequently, the types of problems you will run into are being too busy/ having to control everything, and staff turnover/ finding low-initiative people who have the patience for micromanagement. You will run fewer meetings and issue many more instructions.

If you believe that people can think for themselves and can be trusted with information, autonomy, and decisions, generally you will also be proven correct! The problems you will deal with are coordinating & aligning activity, keeping people informed, and your absence of direct control over the system. You will hold many more meetings and issue fewer instructions.

A manager’s belief system determines how they manage and what types of problems they will encounter as managers.

While I’ve given binary examples here because they flow through easily into behaviours, I want to stay value-agnostic for the moment. This is not about choosing the “best” way to manage or telling you what not to do. Management is a choose-your-own-adventure book and there are few universally correct answers. The secret is that you literally get to choose the types of problems that you/your organisation will have.

Overall, what is most important is that the belief system is tailored to the context and that its owner can live with it. Every management book ever will tell you that people thrive with autonomy and not being micromanaged, but if I am an emergency room surgeon working on a patient who is about to die with some nurses I haven’t worked with before, probably I should be micromanaging! I need the team to do exactly what is required and when.

Good management comes from having a solid belief system for the context of the organisation you run.

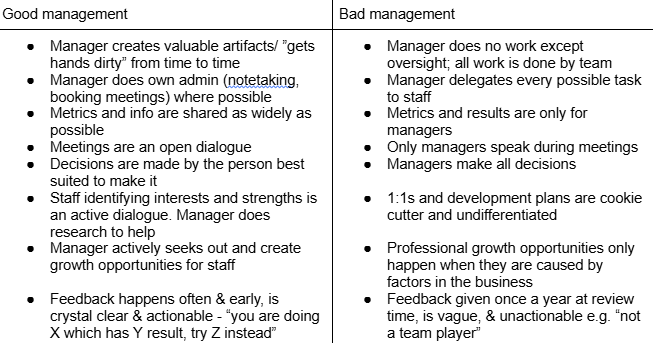

Good management / bad management

Let me take you through a simplified belief system - mine - and then look at what good management looks like in this context. My experience is equity markets/communications & software product. While there are occasional catastrophes - we once had 50% of our revenue turned off overnight - it’s not an emergency room or a nuclear submarine.

If you work in a different field several of your beliefs will be different to mine:

Business is a team sport. We are working together to create disproportionately more value than the sum of our individual efforts.

It is possible to produce an average day’s work in much less than a day. Optimise for productivity in terms of impact per unit of output and reducing the barriers to creating output.

To the extent possible, work should never just “be done” and shipped off to Narnia. Feedback loops are essential especially for internal outputs like decisions, communications, meetings, analysis, training, etc that do not receive market feedback.

High trust is the backbone of an organisation. Actions increase or decrease trust, and this is a feedback loop like anything else.

It is not about you; it is about the team and the organisation.

You cannot control people; you must help them find what they need to succeed and trust them to do their best in the organisation’s best interests.

Every person has potential and value. People live up or down to expectations and it is shockingly cruel to limit somebody else’s potential. Explicitly choose to believe that every person is capable of more and allow people to opt in or out.

All people are flawed. We don’t have the right to expect perfection; we must expect best efforts and a commitment to improving. Feedback must be given quickly and ideally in a way that can be immediately applied.

People go through phases. The organisation must be realistic about its place in the pantheon of individual needs & desires & integrate with these to the extent possible.

As manager, you broadcast to a group of people. You must cultivate personal adequacy and humility because all your flaws and insecurities broadcast too.

Management and leadership are intensely moral disciplines. To cast the aura, you must start from moral high ground, a position of merit, fairness, accountability, respect. You must care, be interested, and be motivated about the work and the people.

Managers have disproportionate ability to introduce decay, waste, injustice, and unhappiness into a system, and consequently must be held to a significantly higher standard of performance and behaviour than ICs. Leaders eat last.

Having defined it, looked at the most common tools, and how they fit into a belief system, we can now start to draw a line between good and bad management for my context.

Let’s imagine a different belief. Say I run a really idiosyncratic, highly independent organisation; maybe something like a stable of newsletter writers. I believe that everyone is responsible for their own work, because it’s not possible to stay across each of their niches & because the market feedback loop is much faster & direct. In this situation, the behaviours might look much more like:

Good management: Manager checks that each creator has a discipline of collecting and measuring feedback, facilitates the sharing of learnings across creators, and checks the integrity of the systems (E.g. that there is a correlation between positive feedback and commercial results).

Bad management: Manager leaves creators to their own devices, ignores/diminishes the importance of learning rate, or checks feedback but is unsystematic/unrigorous, doesn’t facilitate sharing of learnings across the team

No management book will ever tell you “rarely give feedback” or “everyone is responsible for their own development and we do not participate” but those might actually be useful beliefs to have here.

The #1 implication of this is that to manage effectively, an organisation & its managers must settle on a belief system. It must then train, broadcast, and reinforce this belief system to its people and make this an explicit part of its culture.

Once a belief system has been instilled, the types of problems your managers run into will be more uniform and you can start to be effective with training. Your organisation moves beyond a cottage industry with everyone figuring it out for themselves.

Using the writer example above, if you believe that people must be responsible for their own development, what your managers need to excel at is checking system integrity and facilitating the sharing of learnings. Once you have a shared belief system, you can train for that, gaining scale and reducing the time to get up to speed. Sharing best practices becomes easier using a common language.

It also becomes easy to identify “fit” issues where you have (for example) a manager who believes the opposite, and this person is “poisoning the well” / running counter to the culture.

Wrapping up

If you made it this far, thanks for sticking with me. A recap:

Management is the craft of Applying Effort, Adding Leverage, and Solving Problems.

It is a force multiplier on your output, not an output

Your belief system determines how you manage and the types of management problems you will run into

Agreeing on and installing a belief system in your organisation allows you to unify & standardise your management approach, vastly improving quality and making it much easier to train

Thanks for reading.

Fantastic write-up mate. Distills so many books and ideas about managing people into a very short useful summary. The belief system thing is real - naturally, people tend to stick around with other people and organisations that share their beliefs so if you have people that value autonomy and the opportunity to take initiative, they will naturally stick with managers/leaders who let them do that and those that need to be handheld through everything will not last and vice versa. I've encountered both types of leaders and it tends to be the one that surrounds themselves with people who are trustworthy, have a growth mindset and have a healthy degree of humility that seems to have the most successful and high performing unit.